New York City ranked #3 among Orkin’s Top 50 Mosquito Cities list in 2022.

For New Yorkers who own a backyard or enjoy spending time outdoors, this might not be too surprising. Summer in the city is hot and humid. And given our population density, there’s always plenty of humans around for mosquitoes to get their next blood meal from.

Although mosquitoes are known as a year-round pest, their activity typically spikes when temperatures reach 70 °F. Peak mosquito season usually lasts all the way from April until October, and it’s expected to get even longer due to climate change.

Here’s what you need to know about dealing with mosquitoes in New York City including facts, prevention, control, and treatment.

MMPC Mosquito Guide:

Facts about Mosquitoes

There are over 3,000 species of mosquitoes in the world, and approximately 70 of them are known to live in New York.

Contrary to popular belief, most species of mosquitoes don’t bite humans. But of the few species that do, many are vectors of infectious diseases.

Common species of mosquitoes found in New York include:

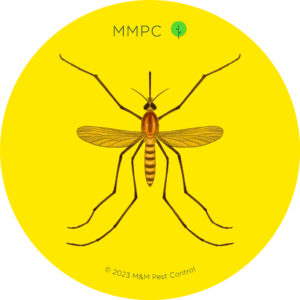

- Northern House Mosquito (Culex pipiens)

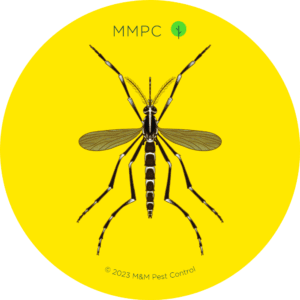

- Asian Tiger Mosquito (Aedes albopictus)

- Yellow Fever Mosquito (Aedes aegypti)

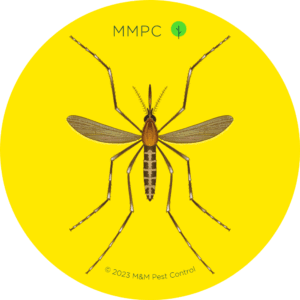

- Eastern Saltmarsh Mosquito (Aedes sollicitans)

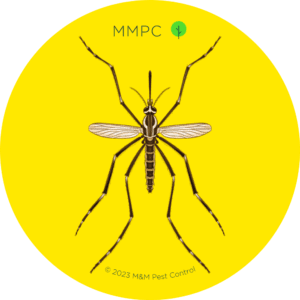

- Common Malaria Mosquito (Anopheles quadrimaculatus)

Life Cycle

The mosquito life cycle involves 4 main life stages: eggs, larvae, pupa, and adults.

Depending on the species, female mosquitoes lay their eggs either in or near sources of water.

- Permanent water mosquitoes, such as Culex pipiens, lay their eggs directly in or around the edges of standing water.

- Floodwater mosquitoes, which includes Aedes albopictus, Aedes aegypti, Aedes sollicitans, and Anopheles quadrimaculatus, lay their eggs above the water line in soil or containers and wait for rain or flooding.

Mosquito eggs may take anywhere from a few days to several months to hatch. The larvae, which live in water, develop into pupae in as little as 5 days and then become adult mosquitoes after another 2–3 days. The entire life cycle, from egg to adult, may be as short as 8–10 days.

The average lifespan of a mosquito is 2–3 weeks, although depending on the species and environment, some adult mosquitoes can survive for several months.

Behavior

- Most mosquito species are crepuscular (most active around dawn and dusk).

- Aedes mosquitoes are also active during the day, while Culex and Anopheles mosquitoes may bite throughout the night.

- Only female mosquitoes bite. A blood meal is required before they can lay their eggs.

- Contrary to what most believe, mosquitoes don’t suck blood to survive. Rather, mosquitoes normally feed on nectar, fruit juices, and plant sap for sustenance.

- Mosquitoes can travel at speeds of 1–2 miles per hour.

What Attracts Mosquitoes?

To avoid getting bitten, it’s important to understand what attracts them to us in the first place (and why they seem to prefer certain people over others).

There are several ways that mosquitoes sense people:

- Heat – Using extremely sensitive temperature-sensing receptors on their antennas, mosquitoes are drawn toward body heat to help them find targets to feed on. People that generate more heat, like joggers or overweight people, are more likely to get bitten.

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) – Mosquitoes can detect the CO2 exhaled in a person’s breath from up to 30 feet away. Heavy breathing, such as during exercise, is more likely to attract mosquitoes.

- Sweat – Mosquitoes are attracted to both water vapor and lactic acid, which are produced when people sweat.

- Dark colors – Research has shown that mosquitoes are attracted to dark colors, particularly black.

- Alcohol consumption – Interestingly, a study in 2002 showed that people who consumed beer were more attractive to mosquitoes than people who did not.

Mosquito Bites & Diseases

The CDC calls mosquitoes the “world’s deadliest animal” for good reason.

Mosquitoes cause more than 700,000 deaths around the world each year through the diseases they carry. While not all mosquito species are disease vectors, the ones that are can carry a variety of devastating diseases.

In 1999, Queens was the center of a West Nile virus outbreak that spread throughout the country. Culex mosquitoes carrying and spreading the West Nile virus continue to pose a threat to New Yorkers today, causing between 3 to 47 cases in the city every year.

In New York City, especially in areas outside the city, potential mosquito-born diseases include:

- West Nile fever

- Zika virus

- Dengue fever

- Chikungunya fever

- Malaria

- Eastern Equine Encephalitis

How to Tell if You Have Mosquito Bites

Sometimes mosquito bites seem to appear out of nowhere on our bodies. That’s because mosquito saliva contains a naturally occurring anesthetic that allows their bites to go unnoticed. Mosquito saliva also contains anticoagulants to prevent blood from clotting, allowing them to get their blood meal quickly.

Reactions to mosquito bites can vary from person to person, but the most common signs are redness, bumps, and itchiness:

- Large, raised bumps that appear puffy and are firm to the touch

- Redness in the skin surrounding the bump

- Itchiness that usually lasts a few days

These are caused by the body reacting to proteins and chemicals in the mosquito’s saliva and typically start to occur within a few minutes after being bitten.

More severe reactions can sometimes occur in children or people with immune systems disorders. These may include fevers, swelling, hives, and swollen lymph nodes.

How to Stop Mosquito Bites from Itching

Mosquito bites itch because proteins in mosquito saliva cause your immune system to release histamines, which trigger the itch receptors in your skin.

If left alone, the itchiness usually dissipates within a few hours to a couple of days. However, scratching at the bite will make it last longer.

One of the first things to do after realizing you’ve been bitten by a mosquito is to avoid scratching the area. According to scientists at the NIH, scratching an itchy bite causes your body to release serotonin. This chemical, which normally helps narrow arteries to clot blood and heal wounds, also triggers receptors on itch-transmitting nerve cells, causing your itch to feel worse.

In addition to stopping yourself from scratching, the Mayo Clinic recommends these methods you can try at home to stop mosquito bites from itching:

- Use anti-itch medicines such as calamine and hydrocortisone, which can be applied as lotions, creams, or pastes to alleviate itching.

- Apply a cool compress. Cold temperatures provide a numbing effect around the bite, and can help decrease swelling.

- Take an oral antihistamine for stronger reactions. Antihistamines directly block histamine receptors to reduce the itchy sensation you feel. You can find nonprescription antihistamines such as Benadryl at most pharmacies and drug stores.

Other Home Remedies for Mosquito Bites

- Baking Soda – Mix 1 tablespoon of baking soda with 3 tablespoons of water to form a paste. Dab the paste over mosquito-bitten areas and let it sit for 10 minutes before rinsing.

- Oatmeal – Mix equal parts oatmeal and water into a spackle-like substance. Apply it over the skin for 10 minutes, then wipe it off.

- Aloe Vera – Apply aloe vera gel over the bite.

- Honey – Apply a small drop of honey directly over the bite.

- Basil – Boil 2 cups of water with half an ounce of dried basil leaves. After the mixture cools, dip a washcloth into the liquid and rub it gently on the irritated skin.

- Tea – Soak a bag of green or black tea and cool it down in the fridge. Apply the cold tea bag over the bite.

- Rubbing alcohol – Clean the skin around the bitten area with rubbing alcohol, which has a cooling effect that helps relieve itching as it dries. However, be careful to avoid using too much, which can cause further irritation.

Prevention: How to Keep Mosquitoes Away

These annoying pests can be difficult to get rid of once they’ve established themselves on your property. A single adult female can lay up to 300 eggs in a single batch, which means you might have dozens—or even hundreds—of new mosquitoes hatching every day.

Effective mosquito control starts with prevention, especially in areas around stagnant water.

Mosquitoes require stagnant water to lay their eggs. By eliminating sources of water, you can slow or stop mosquitoes from breeding and reproducing.

Disney World is a prime example of successful mosquito prevention. Despite being built on humid swampland, there are virtually no signs of these pests. That’s because the water inside the parks is always flowing from one place to the next through a vast network of drainage ditches—it’s never allowed to stagnate anywhere. Even the buildings and landscaping choices are strategically designed to prevent water from collecting.

Tips to Prevent Mosquitoes Outside Your Home

- At least once a week, empty and clean out any outdoor items that can hold water, such as chairs, tables, cans, bottles, buckets, flowerpot saucers, and trash cans.

- Regularly clean and change the water in birdbaths and pools.

- Ensure that all water storage containers are tightly covered.

- Use mosquito dunks or mosquito bits to treat large containers with water that cannot be covered or emptied.

- Clean your gutters regularly to eliminate clogs that may cause water to build up.

- Avoid overwatering your lawn or garden.

- Clear leaf piles and other debris.

- Grow certain plants that naturally repel mosquitoes, such as citronella, lemongrass, lemon balm, lemon thyme, rosemary, lavender, mint, and catnip.

- Add certain fish species that eat mosquito larvae to outdoor ponds, such as mosquito fish, goldfish, guppies, and koi.

Tips to Prevent Mosquitoes from Getting Inside

- Avoid leaving doors and windows open.

- Install window and door screens.

- Identify and fix other potential entry points, such as cracks and holes in walls and doors.

- Seal gaps around screens and underneath doors.

- Place mosquito-repelling plants near doors and windows.

Mosquito Repellants

If you’re planning to spend time outdoors during mosquito season, a strong, long-lasting repellent will help protect you from getting bitten. The CDC recommends using mosquito repellants containing these ingredients:

- DEET

- Picaridin

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus (sometimes referred to as OLE or PMD)

- IR3535

- 2-undecanone

Oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE), PMD, IR3535, and 2-undecanone are considered biopesticide repellents, which means they are derived from—or are synthetic versions of—natural products.

Studies have shown that the most effective active ingredients are DEET, picaridin, and IR3535. Among these chemicals, DEET is the oldest and generally considered the gold standard for mosquito repellents.

The most effective DEET mosquito sprays are:

If you have dogs or cats at home, and you want to know which mosquito sprays are safe with pets around, check out our list of pet safe mosquito sprays.

It’s important to note that all of the chemicals and products mentioned are well-studied and proven to be safe, but you should always follow the instructions on the product label to determine when and how much to use.

About MMPC: NYC’s Top-Rated Mosquito Control Experts

Need help keeping your home or property mosquito-free this summer?

MMPC has over 25 years of experience providing effective and eco-friendly mosquito solutions. We offer comprehensive outdoor treatment programs designed to exterminate mosquitoes and stop them from coming back.

Learn more about our eco-friendly mosquito control services!