MMPC Field Guide: Ticks

Ticks are blood-feeding arachnids—eight legs, no wings, and specialized mouthparts made to pierce skin and stay latched. They’re active in the New York area from April through November and known carriers of disease.

Some species stay on one host through all life stages. Others drop off and find new hosts between molts.

Biology

Ticks thrive in shady, covered areas such as wooded trails, overgrown brush, tall grass, and leaf litter. You won’t find many in open lawns or dry, sunny spaces. They “quest” by crawling up vegetation and extending their front legs, waiting to grab onto anything that passes by. They detect hosts by sensing movement, heat, and carbon dioxide.

Once on a host, they move to spots with thin skin or folds—behind the knees, underarms, groin, scalp, ears, belly button—and dig in.

After feeding, the female drops off and lays eggs in leaf litter. One batch can contain thousands. The eggs hatch into six-legged larvae, or seed ticks, which feed on small animals like mice or birds. Then they drop off, molt into nymphs, and feed again. After the next molt, they become adults and look for bigger hosts. The life cycle takes 2 to 3 years.

Risks

A tick bite doesn’t usually hurt. The danger comes from what they may transmit. Different species in the Tri-State Area carry different pathogens:

- Blacklegged ticks (deer ticks): Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Powassan virus

- American dog ticks: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia, tick paralysis in dogs

- Lone star ticks: Ehrlichiosis, tularemia, Heartland virus, Bourbon virus, alpha-gal syndrome (can trigger red meat allergy)

Ticks become infected when feeding on an infected host as larvae or nymphs. When they feed again, they pass those pathogens along. Their saliva contains natural anesthetics, which makes most bites go unnoticed.

Identification

Ticks are arachnids. They have eight legs, no wings, and no antennae. The head and thorax are fused into one part called the capitulum, which holds the mouthparts.

Most of what we see around homes are hard ticks. They’ve got a hard plate on the back called a scutum. On females, the scutum is small so the body can expand while feeding. On males, it covers most of the back and doesn’t stretch.

Unfed adults are about 2–3 mm (¹⁄₁₆″ to ⅛″) long; around the size of an apple seed. After feeding, females can swell up to 15 mm (¹⁹⁄₃₂″). Nymphs are much smaller; 1–2 mm, about the size of a poppy seed.

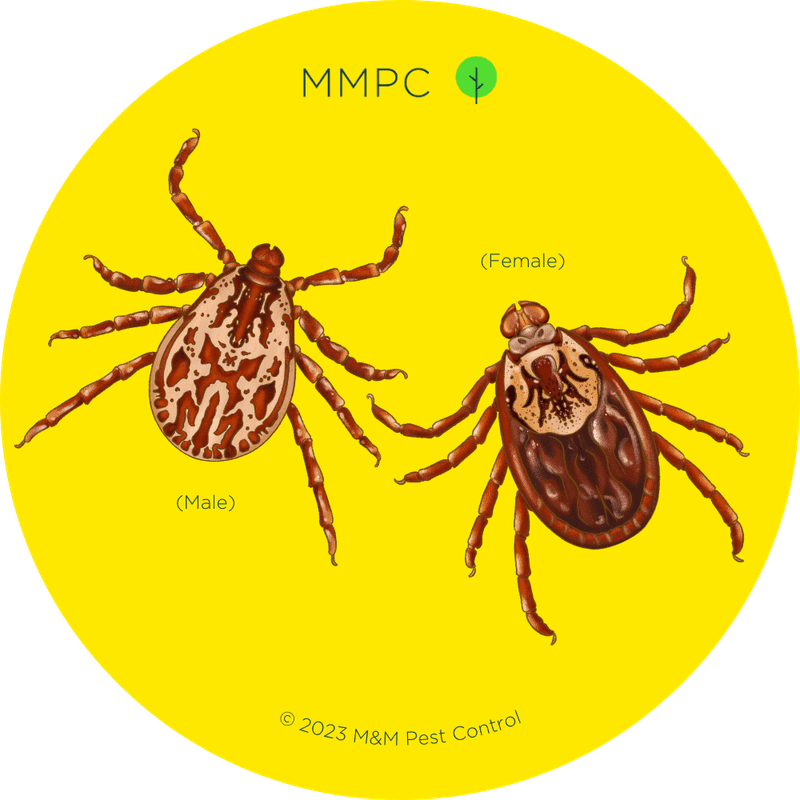

American Dog Tick / Wood Tick

Dermacentor variabilis

The American dog tick is widely distributed east of the Rocky Mountains. Common in grassy and brushy areas, especially along paths and field edges. Adults are most active spring through mid-summer, peaking in May and June.

Young stages feed on small mammals like rodents. Adults prefer medium to large mammals; frequently found on dogs, but also bite cats, deer, and humans.

Carries Rocky Mountain spotted fever and tularemia in the eastern U.S.. Does not transmit Lyme disease. Can cause “tick paralysis” in pets or children if attached at the base of the skull.

Key ID Features

- Adults are 3–5 mm (⅛″–³⁄₁₆″) unfed, up to 15 mm (¹⁹⁄₃₂″) when engorged.

- Brown to reddish-brown with ornate shield marked with silvery-white or cream patterns

- Males have extensive silver-gray patterns; females have smaller shield with pale “halo”

- Broad, oval body with rectangular head and short mouthparts

- Festoons present, 11 small “pie crust” indentations at rear

- Visible eyes appear as pale spots on each side of shield

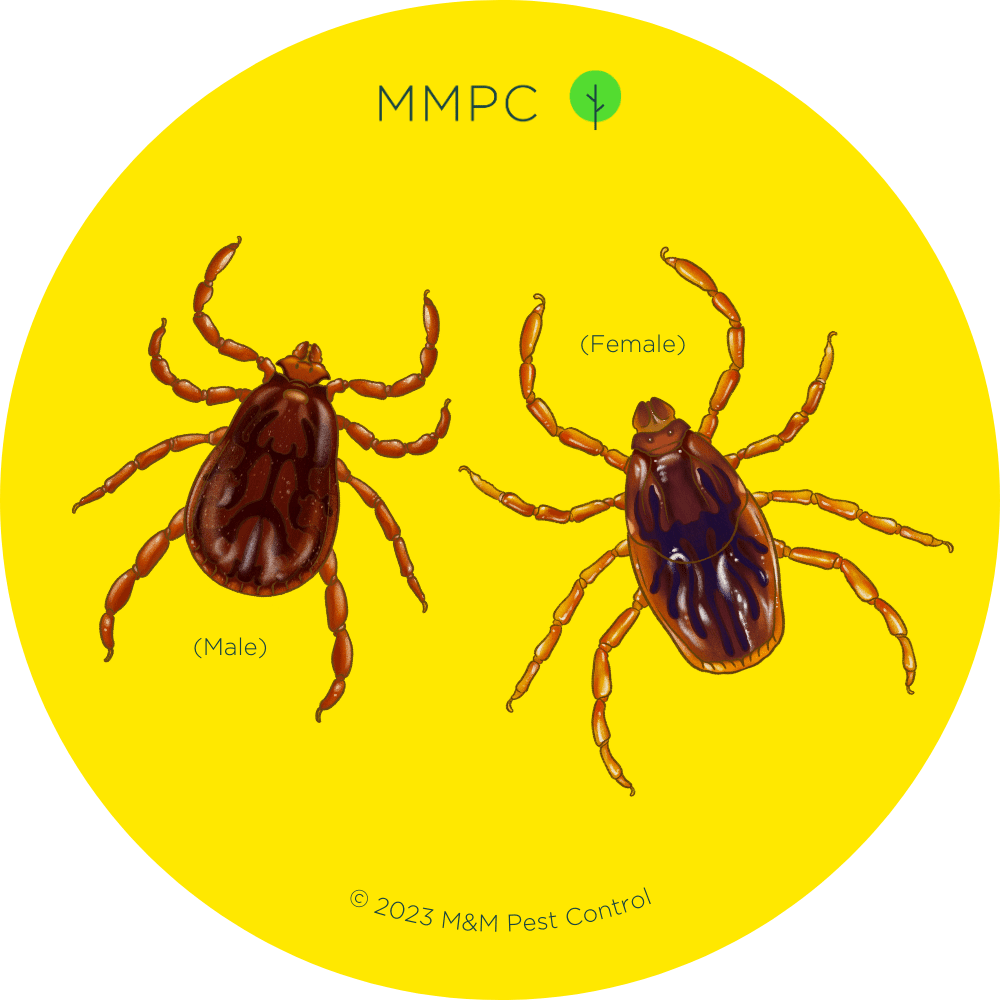

Brown Dog Tick

Rhipicephalus sanguineus

The brown dog tick is unique; specially adapted to living indoors with dogs. Found worldwide in warmer climates. In the northeastern U.S., they’re mainly in dog boarding facilities, shelters, or infested homes. Rare outdoors, especially in cold climates.

All life stages prefer to feed on dogs, rarely bites humans. Can breed indoors year-round, so infestations build quickly if not addressed. May be found crawling on walls, in cracks, or on dog bedding.

Spreads canine ehrlichiosis and babesiosis. In southern U.S., can transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever to humans.

Key ID Features

- Adults 2–3 mm (¹⁄₁₆″–⅛″) unfed, up to 12 mm (½″) when engorged.

- Uniform reddish-brown to tan color; no distinct markings

- Elongate oval body with hexagonal (six-sided) head when viewed from above

- Short, triangular mouthparts

- Festoons present but smaller than American dog tick

- Plain brown tick; lacks contrasting markings

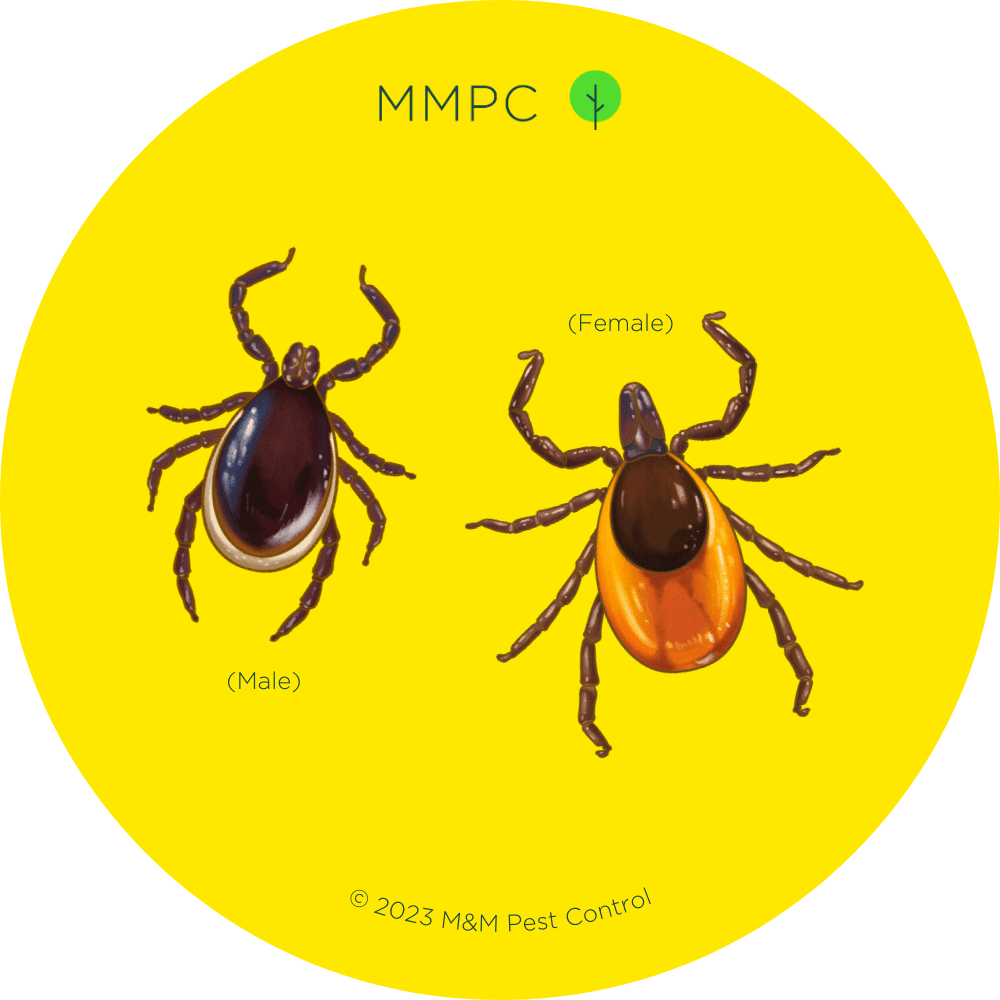

Deer Tick / Eastern Black-Legged Tick

Ixodes scapularis

The deer tick is the most important disease-carrying tick in the Eastern U.S. Has a two-year life cycle with different activity patterns by life stage.

Nymphs emerge in late spring and are active through summer (May to August). Adults emerge in fall and again early spring, can be found October through May whenever temperatures rise above freezing. Feed on many different hosts: young stages bite mice, small mammals, and birds; adults prefer larger animals like deer but will attach to people and pets.

Main carrier of Lyme disease. Also transmits anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and Powassan virus. Lyme disease is most commonly transmitted by nymphs in early summer, but adults can transmit Lyme and other illnesses in fall or spring.

Key ID Features

- Adults 2–3 mm (~¹⁄₁₆″–⅛″) unfed, up to 10–13 mm (½″) when engorged.

- Dark brown to black overall; females have orange-brown abdomen with contrasting dark brown shield

- Males uniformly dark brown with shield covering whole back

- Legs typically dark brown or black (hence “blacklegged” tick)

- Broad oval body with noticeably long, narrow mouthparts

- No festoons, smooth rear edge

- No eyes or patterns

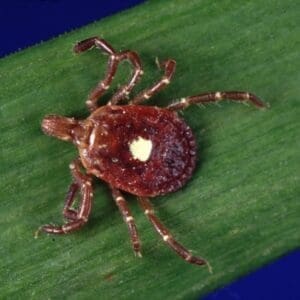

Lone Star Tick

Amblyomma americanum

The lone star tick is an aggressive woodland tick common in the Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic U.S., now extending northward into parts of New Jersey, New York, and southern New England. Lives in forests with dense underbrush and edge areas where deer and other hosts frequent.

Feed on variety of hosts at all life stages. Active in spring and summer (roughly April through August) with adults and nymphs most common in late spring/early summer. Known for aggressive biting behavior—adults will actively chase or crawl rapidly toward hosts.

Main carrier of Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis and can transmit tularemia. Also spreads Heartland virus and Bourbon virus. Bites can cause alpha-gal allergy syndrome (immune reaction to red meat products). Also associated with STARI (Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness), a Lyme-like rash.

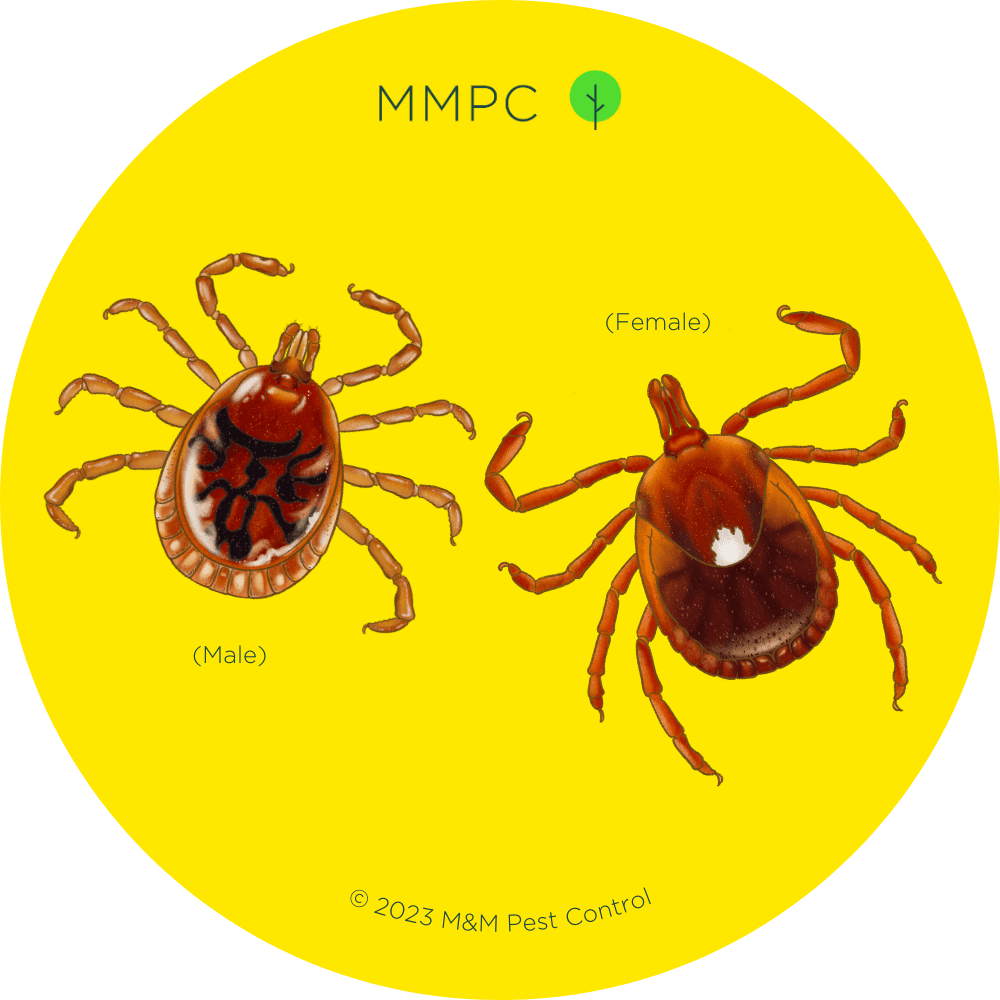

Key ID Features

- Adults 3 mm (~⅛″) unfed, up to 15 mm (¹⁹⁄₃₂″) when engorged.

- Reddish-brown body with different markings on males and females

- Females: Single distinct silvery-white dot in center of shield (the “lone star” spot)

- Males: Lack single spot but have scattered whitish streaks or spots along shield edges

- Oval body with small head and long, sturdy mouthparts

- Festoons present; eyes on sides of shield

- Generally more robust and larger than deer ticks; lack dark black legs

Asian Longhorned Tick

Haemaphysalis longicornis

Recently introduced invasive species first identified in New Jersey in 2017.

Major concern for livestock and wildlife; known to form massive infestations on cattle, sheep, and other hosts, causing anemia and weakness. Female Asian longhorned ticks can reproduce without mating (parthenogenesis), allowing rapid population growth. Hundreds or thousands may be found on a single animal.

In the U.S., has not been proven to transmit human diseases, but capable of carrying pathogens. Lab studies indicate U.S. populations could spread Powassan virus, Heartland virus, and Rickettsia.

Key ID Features

- Adults 2–3 mm (¹⁄₁₆″–⅛″) unfed, up to 9–10 mm (⅜″) when blood-fed.

- Uniform light brown to buff-tan color; plain shield with no markings

- Oval and somewhat flattened body with short, broad mouthparts

- Mouthpart appendages (palps) flare out at base, giving distinctive angular look to sides of head

- Festoons present; lack eyes

- Easily mistaken for brown dog ticks due to size and color

Control

Getting rid of ticks takes more than one approach. You need to understand where they live and breed, then cut off what they need to survive. Unlike indoor pests, ticks mainly develop outdoors (except brown dog ticks). The aim is making your yard less welcoming to ticks and avoiding contact when you venture into their territory.

Prevention

Yard Maintenance

- Cut your grass short regularly.

- Trim overgrown shrubs and low-hanging tree branches to let sunlight reach the ground

- Rake up leaf litter and debris piles, especially in shady areas

- Install a 3-foot gravel or wood chip barrier if you border woods. This acts like a dry moat that ticks won’t cross

Wildlife Control

- Fence out deer or use repellents. A single deer can carry hundreds of ticks and transport them across large distances

- Don’t feed deer, secure garbage. Artificial food sources attract deer and concentrate tick populations in residential areas

- Pull bird feeders that bring in tick-carrying critters

- Seal gaps under decks and sheds where mice nest. Consider bait stations in outbuildings

Personal Protection

- Use light-colored long sleeves and long pants. Tuck pants in socks

- Treat clothes with permethrin spray, this kills ticks on contact and remains effective through multiple washes

- Apply EPA-approved bug repellents with DEET (20-30% concentration), picaridin, or IR3535 on exposed skin. Follow label directions

- Tick check and shower within 2 hours of coming indoors. Use handheld mirror to check hard-to-see areas

Natural Tick Control

Natural methods work slower than chemicals but offer safe options around kids and pets. These approaches work best when combined with other tick control strategies:

- Beneficial Nematodes: Microscopic worms that go after ticks in soil. Mix with water and spray in infected areas. May take several weeks to show result

- Diatomaceous Earth (DE): Drying powder that dehydrates ticks. Use food-grade DE only. Apply barely visible layers in tick-prone areas, gardens, wall voids

Chemical Treatments

For serious infestations, you need acaricides (tick killers). Synthetic pyrethroids like bifenthrin work well. Target yard edges next to woods, shaded flower beds, around shrubs, and under decks. Don’t waste product spraying sunny lawn areas where ticks rarely go.

Products containing bifenthrin or cyfluthrin knock down ticks quickly. These synthetic pyrethroids kill on contact and keep working for weeks. Hit ticks twice a year when they’re most active. Spray in late May to catch the tiny nymph ticks coming out, then again in early October when adult ticks start looking for final blood meals before winter.

Only treat if you’re adjacent to woods or dealing with a known tick problem. Follow labels carefully. If unsure, consider hiring professionals for precise application, especially near water sources or sensitive areas.

Frequently Asked Questions

How to remove a tick?

Found a tick on you or your pet? Stay calm. Here’s what you should do:

- Clean fine-tipped tweezers with rubbing alcohol first

- Grab the tick by its head/mouthparts, close to skin. Don’t squeeze the fat body part.

- Pull straight up with steady pressure. No twisting or jerking.

- Clean the bite with alcohol or soap and water.

- Put the tick in a jar with the date. Your doctor might want to see it later.

The bite might look red for a day or two. That’s normal. But watch for a spreading rash, fever, headache, or flu-like symptoms over the next few weeks. Call your doctor right away if any of these develop.

READ MORE: How to Remove a Tick

How long must a tick be attached to transmit disease?

It’s not instant, which is good news. Disease germs live in the tick’s stomach and have to travel to its mouth before they can infect you. That takes time.

- Lyme disease: Usually needs 36-48 hours attached

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever: Can happen in 6-20 hours

- Anaplasmosis: Around 24+ hours

- Babesiosis: Same as Lyme disease, 36-48 hours

- Powassan virus: The scary one. Can transmit in just 15 minutes, but it’s rare

Important: These timeframes aren’t guarantees. Some people get sick faster, others slower. When in doubt, see a doctor.

Can ticks infest my home?

Most can’t. Outdoor ticks need high humidity to survive and reproduce. They may hitchhike inside on clothing or pets, then dry out and die within days unless they find another host.

Brown dog ticks are different. They’ve adapted to indoor life and can complete their entire life cycle inside. If you have dogs and notice small brown ticks crawling on walls or in cracks, you have a breeding population. This requires professional treatment.

Are ticks active in winter?

Not all of them. Many go dormant, but adult deer ticks stay active on warm winter days. Antifreeze compounds protect their bodies, and they hunker down under leaf litter when it’s cold. Regardless of season, we recommend to keep pets protected year-round as per your vet’s advice.

Our Services

Some tick problems are too big for DIY solutions. If you’ve got ticks in wall voids, a confirmed indoor breeding population of the Brown Dog Tick, persistent infestations, or structural issues, call the pros. MMPC handles serious tick problems with targeted treatments that reach places you can’t.

- Professional Insecticide Application

- Heat Treatments

- Fumigation